The entire world is in a housing crisis at the moment. And at times, it might seem like this has been going on for almost two decades, ever since the financial crisis of 2008.

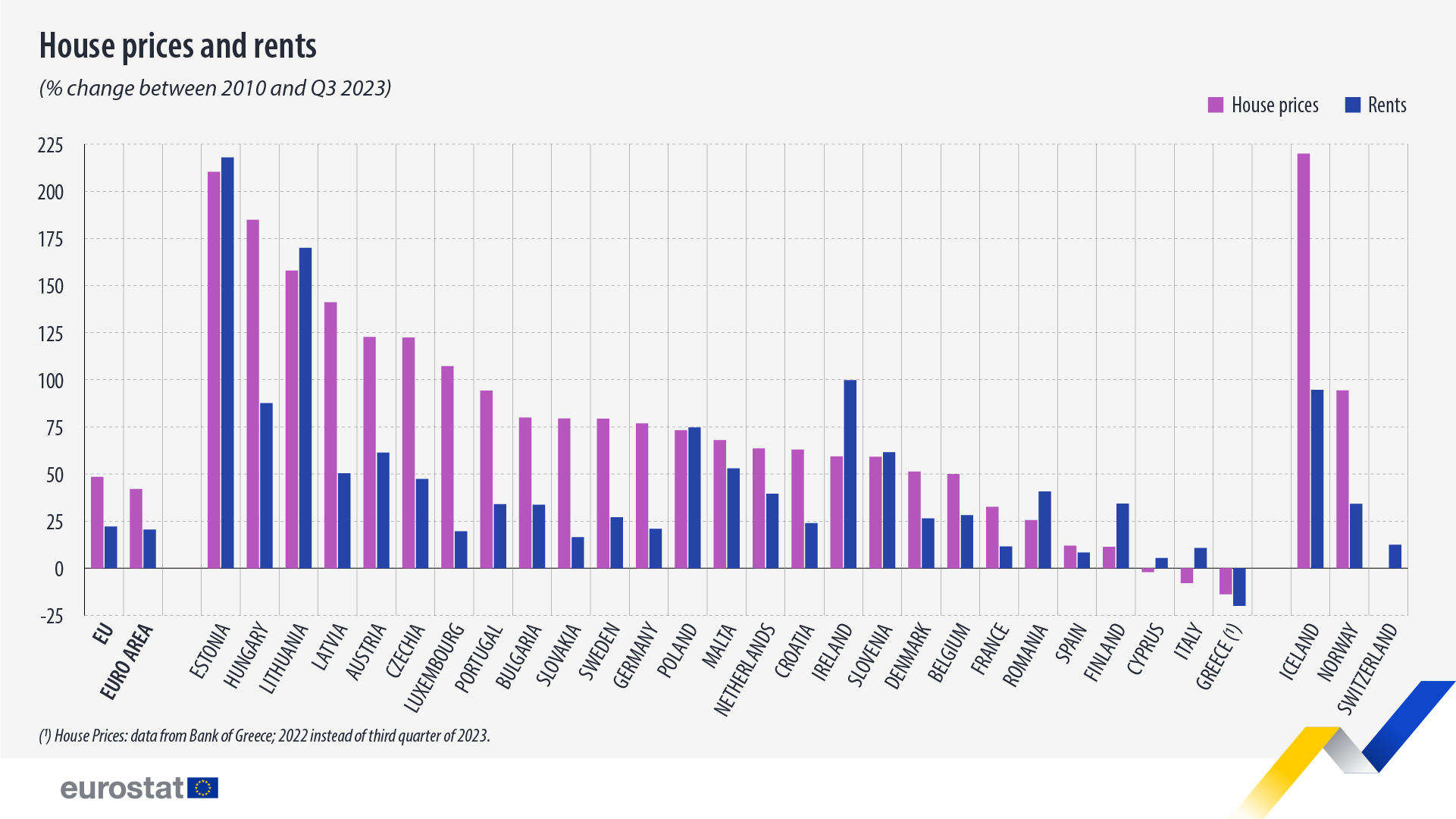

Housing prices in the EU have risen sometimes over 100% between 2010 and 2023, with the fastest increases in Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, and Austria, only decreasing in Greece, Italy and Cyprus, according to the Eurostat [archived version].

Considering this, the usual tendency is to buy a house as soon as one can afford it, and consider this an “investment”. This will also result in not having to pay rent to a private landlord for living in one of their properties. This is great, generally speaking, as many see landlords as parasitic.

There are, of course, several problems with this. Second Thought has a video on landlords. But, in summary, the reason landlords have a property is that others don’t. Housing is a finite resource, after all.

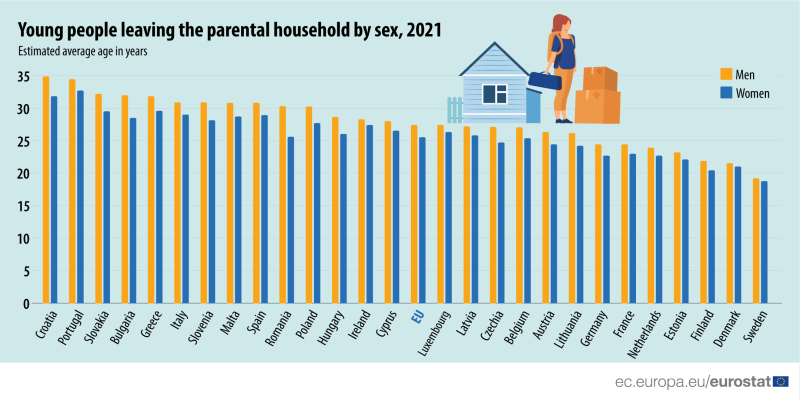

The Almería University published an article [archived version] on the age of young people leaving their parental household across Europe.

It is very apparent how, the richer a country is, the earlier one leaves the parental household on average. The difference is quite stark, too, with Croatia having an average age of 35 for men, which means more than a decade of working and paying taxes, whereas in Sweden it is under 20, which means many university students will leave their home even before graduating. This is unprecedented.

Besides this, it is also interesting to see how the rates of home ownership in poorer EU countries like Hungary, Slovakia, or Poland is higher than in some rich countries like Austria, Denmark, or Switzerland.

These two factors combined mean that, while people in poorer countries leave their parent’s home later, they usually buy, whereas people in richer countries leave their parent’s home sooner, but rent.

The usual route for renting a home is to rent from a private landlord. Either a corporation that owns an entire building complex, or a family that has a second home they bought to receive passive income from rent. However, that’s not all that exists.

Renting around the world

In some cities, like Vienna, public housing is not just for poor people or marginalised communities, but a reality so tangible that it drives private housing development prices down, as the public houses are not worse in quality than the private market.

As such, landlords don’t have a big incentive to charge exorbitant rents, because they’re competing against high-quality housing in the public sector. And people who rent have more choice and more leverage.

Amsterdam is another city that applies rent control mechanisms, with 75% of the rental market consisting of social housing. Rents in Amsterdam are capped based on a points system that takes into consideration factors such as location, energy efficiency, and amenities. Copenhagen also uses a points system, and it strictly regulates buildings constructed before 1991 to maintain their affordability, without impeding recent developments that may have a higher price in the private housing market.

The benefits of home ownership

Of course, perhaps, one massive drawback of public housing is, while the rents are low, you never own that home, because it belongs to the government. This is, strictly speaking, true. But this may not matter as much as people think it does.

I believe that we have been taught to believe that owning your home is an investment, and it offers a safety guarantee against evictions due to not paying rent. Furthermore, it enables you to buy more properties in the future and rent some of them to generate a passive income, for retirement or to supplement your pension.

The problem with this logic is that it perpetuates exploitation. Exploitation by the capitalists and petite bourgeoisie against the younger generations, immigrants, and people with fewer means or who cannot get a mortgage.

Landlords are hated, and there is a lot to be said about the way they abuse their position in society against the less financially able. I find it egregious and unacceptable that a corporation can buy (or build) a block of apartments and then make profit through charging rent, for, often, very little service offered, as utilities are not included, and, in seeking to maximise profit, these corporations will try to repair as few things as possible, and only to the extent the law requires them to. It makes sense: companies exist to turn a profit through spending as little as possible, and receiving as much income as possible to have a net positive balance. The more repairs a housing corporation performs, the less profit it earns. So the system incentivises these companies to blame the tenant for every repair and problem instead of fixing this themselves.

With private families the situation is similar, with the key difference these families will often not have a legion of lawyers just to allow them to tread the sometimes fuzzy line between repairs that are responsibility of the landlord, and those repairs that are the responsibility of the tenant, thus, common sense will play a part here when deciding when to carry repairs out.

In a situation where it’s the government who manages the rental units, there is an incentive to offer good quality housing at affordable prices; especially in democratic countries. As a bad performance for social housing can simply mean the government gets voted out of office. Nobody likes low-quality overpriced housing other than landlords. And this is where the issue lies, I think. Misaligned incentives, where landlords are trying to maximise profit, and renters are trying to maximise savings. A landlord is not required, and will likely never take the side of the renter. Landlords are running a business, not a charity. With a government running this, things would be much different.

What’s left for renters?

Because of a variety of factors, renters often have very little leverage and choice over the type and quality of housing unit they can rent.

For example, landlords often only provide renters with the year of construction and allow them to observe with their own eyes during the inspection. But if, for example, the landlord didn’t invest in solar panels, the electricity bill could prove costly. Even where the landlord allows the renter to install solar panels, these are an expensive investment, and installing and uninstalling them when moving out can cost hundreds of dollars, plus transportation, and the chance for these panels to break during work increases.

This is quite a perverse system, and the reality, as Vienna shows, is that it doesn’t have to be. Housing can be affordable with the adequate policies in place. Public housing can be accessible, high-quality, and stable for the long term. This is not only not some sort of utopian world, but the reality in many parts of the world.

However, because in many cultures this “need” to own a house is more or less ingrained in the society and culture, this will mean that a considerable portion of the population will be landlords or own their home, which makes rent control and public housing projects unfeasible, as there is no logical reason for most people who bought an expensive house to allow themselves to be undercut by a government programme. The people who already own a house will think of themselves as hard workers, and seek to confirm their biases by considering most people who don’t own a house are young or lazy (for a definition of “lazy”, naturally).

If countries ever wish to tackle the never-ending housing crisis, a drastic culture change is required. Housing must stop representing a safe investment while simultaneously making it attractive for newer housing units to be built. Or perhaps the government takes complete control of this and forces the private market to compete against high-quality affordable housing, inevitably driving prices down.